With all the attention on Valeant lately it has reminded me of Buffett’s Salomon adventure. No, I am not saying these two situations are “exactly” the same but there are a ton of similarities. For those who want the crib notes:

1- Buffett made his largest single investment ever in a company when he put $700M into Salomon (~$1.25B today)

2- That was 1987 and Buffett also took a seat on the Board

3- In 1990-91 Salomon traders broke the law in rigging Treasury auctions (details below)

4- Where it not for Buffett agreeing to help run it, Salomon would have probably filed Chapter 11 as the NY Fed was about to cut it off and his entire investment then lost as it was levered ~33-1 at the time (Lehman at its collapse was only 30-1).

From Fortune (full article here)

HOW IT BEGAN

That Sunday in August was a far cry from the commercialism of another Sunday, Sept. 27, 1987, when Buffett and John Gutfreund, then Salomon’s chairman and CEO, agreed that Berkshire Hathaway would buy $700 million of Salomon convertible preferred stock, which equated to a 12% stake in the company. The deal allowed Gutfreund to stave off takeover artist Ronald Perelman, who seemed poised to buy a large block of Salomon common stock from certain South African investors wanting to sell. With Berkshire’s $700 million, Gutfreund was able to strike a deal that allowed Salomon itself to buy the South African stock–and with that, Perelman was dispatched.

It was easy to see why Gutfreund welcomed Warren Buffett, White Knight. It was less easy to see why Buffett wanted to hook up with Salomon, much less trust it with this mint, $700 million–the largest amount he’d ever invested in a single company. Over the years, Buffett had derided investment bankers, deploring their enthusiasm for deals that provided huge fees but that were turkeys for their clients. He has also spoken often of wanting to work only with people he likes. So here he was, handing over mountains of Berkshire’s carefully accumulated and husbanded cash to the high-living, cigar-chomping, corner-cutting crowd soon to be made infamous in Liar’s Poker?

Several reasons explain the move, none of them really good enough in the light of what followed. One is that Buffett had been having trouble for a couple of years finding stocks he thought reasonably priced and was looking for fixed-income alternatives. A second is that the Salomon proposal came from John Gutfreund, whom Buffett had seen do principled, non-greedy, client-friendly work for GEICO, in which Berkshire was then a major stockholder (and which is now owned 100% by Berkshire). Buffett liked Gutfreund–still does, in fact.

A third explanation was simply that Buffett thought the terms of the deal worth accepting. In effect, convertible preferreds are fixed-income investments with lottery tickets attached. In this case, the security was to pay 9% and be convertible after three years into Salomon common stock at $38 a share–against the $30 for which the stock had been selling. If Buffett did not convert the stock, it was to be redeemed over five years beginning in 1995. To Buffett, it looked like a decent proposition. “It’s not ‘a triple,’ which is what you’d like to have,” he said to me in 1987, “but it could work out okay.”

To some of the brainy, mathematical types at Salomon, that appraisal would have qualified as the understatement of the year. From Day One, they thought–and let it be known to the press–that Buffett had exploited Gutfreund’s fear of Perelman and had secured a dream security, with a too-high dividend or a too-low conversion price or some combination thereof. Over the next few years, this opinion did not die at Salomon, and more than once executives of the firm (though never Gutfreund) came to Buffett with propositions for deep-sixing the preferred.

It’s fair to say that Buffett might have taken those offers more seriously had he known that ahead lay the business-wrecking, profit-shredding scandal that broke in August 1991–and that turned the world upside down for both Salomon and him.

A little stage setting here: Before the crisis hit, Salomon was on its way to an excellent business year, marred only by a Treasury investigation into a May T-bill auction in which Salomon was thought perhaps to have engineered a short squeeze. Despite that sticky matter, Salomon’s stock had climbed to $37 a share, a price very near Buffett’s conversion point of $38.

THE PHONE CALL

For the story of what then happened, we may begin with Buffett in Reno. Yes, Reno, which was the spot two executives of a Berkshire subsidiary had picked for an annual getaway with Buffett. Arriving in Reno on the afternoon of Thursday, Aug. 8, Buffett checked with his office and found that John Gutfreund, en route at that moment from London to New York, wanted to talk to him that evening. Gutfreund’s office said he’d then be at Salomon’s principal law firm, Wachtell Lipton Rosen & Katz, and Buffett agreed to call him there at 10:30 P.M. New York time.

Mulling this over, Buffett concluded that it couldn’t be bad news, because Gutfreund hadn’t been in New York to attend to it. Maybe, he thought, Gutfreund had made a deal to sell Salomon and needed a quick okay from the directors. Heading out to dinner in Lake Tahoe, Buffett actually told his group that he might be hearing “good news” before the evening was out–a characterization indicating Buffett was ready to bail from this supposedly plummy deal he’d got into four years earlier.

At the appointed time, breaking from dinner, Buffett stood at a pay phone to make his call. After a delay, he was put through to Salomon’s president, Tom Strauss, and its inside lawyer, Donald Feuerstein, who told him that because Gutfreund’s plane had been held up, they would instead brief Buffett on “a problem” that had arisen. Speaking calmly, they said that a Wachtell Lipton investigation commissioned by Salomon had discovered that two of its government securities traders, including the top gun, managing director Paul Mozer (a name Buffett didn’t know), had broken the Treasury’s bidding rules on more than one occasion in 1990 and 1991.

Mozer and his colleague, said Strauss and Feuerstein, had been suspended, and the firm was now moving to notify its regulators and put out a press release. Feuerstein then read a draft of the release to Buffett and added that earlier in the day he had talked at some length to Salomon director Charles T. Munger, Berkshire’s vice-chairman and Buffett’s sidekick in everything important.

The release contained only a few details about Mozer’s sins. But a fuller account dribbled out over the next few days, depicting a man at war with the Treasury over bidding rules that he despised. A new rule, promulgated in 1990 to prevent such behemoths as Salomon from cornering the market, said that a single firm could not bid for more than 35% of the Treasury securities being offered in a given auction. In December 1990 and again in February 1991, Mozer simply made hash of this rule by, first, bidding for Salomon’s allowable of 35%; second, submitting, without authorization, separate bids for certain customers; and, third, simply stuffing the securities that these bidders won into Salomon’s own account, never telling the customers a word about the whole exercise. From all this, Salomon emerged with more than 35% of the auctioned securities and with increased power to swing its weight around.

On that Thursday night, with other pay-phoners chattering all around him, Buffett did not hear nearly that much detail nor detect, in Strauss and Feuerstein’s matter-of-fact tones, any reason to be particularly alarmed. So he went back to dinner.

Only on Saturday, when he reached Munger, then vacationing on a northern Minnesota island, did Buffett get a sense of real trouble. Munger, a lawyer by training, had stopped Feuerstein’s recital two days earlier to explore what Feuerstein meant by saying–to use the words that were on a sheet of “talking points” drawn up by lawyers for these calls–that “one part of the problem has been known since late April.” In writer-speak, that is the “passive voice,” and it raises an obvious question: “Who knew?”

Munger bore down on that question and found out that Mozer, believing that he was about to be unmasked, had disclosed the February bidding infractions to his boss, John Meriwether, in late April. Calling Mozer’s behavior “career-threatening,” Meriwether immediately went to Strauss with the news and, days later, met with Strauss, Gutfreund, and Feuerstein to decide what to do. Feuerstein advised the others that Mozer’s act was probably “criminal,” and the group concluded that the New York Federal Reserve must be told what had happened. But then no one did a thing about telling–neither in April nor in May, June, or July. That was the inaction that Buffett later said was “inexplicable and inexcusable,” and that pushed the crisis to its limits.

Talking to Buffett on that Saturday, Munger called management’s extended failure to act “thumb sucking,” which is a term Buffett thinks he heard repeated when he himself was talking to Strauss and Feuerstein. But he does not otherwise think the two men made any effort to clearly inform him about top management’s part in this mess. Some of Salomon’s regulators later voiced a similar complaint, saying they were told about top management’s dereliction, but in soft, shrouded words that failed to get the point across.

Even so, that left them better off than the public, which in the Aug. 9 press release learned absolutely nothing about management’s having known anything, at any time. In his phone conversation with Feuerstein, Munger sharply challenged the omission. But Feuerstein said that management and its lawyers worried that too much disclosure would threaten the firm’s “funding”–its ability to roll over the billions of dollars of short-term debt that became due every day. So Salomon’s plan was to tell its directors and regulators that management had known of Mozer’s misconduct, but to avoid saying this publicly. Munger didn’t like it, finding this behavior neither candid nor smart. But not considering himself an expert on “funding,” he subsided.

When he and Buffett talked on Saturday, however–with the Salomon story played big on the front page of the New York Times–they resolved to insist on prompt disclosure of the full facts. On Monday, Munger delivered their strong opinions to Gutfreund’s close friend and adviser, Martin Lipton of Wachtell Lipton, and was told that the matter would be discussed at a telephone board meeting scheduled for Wednesday afternoon. Buffett, meanwhile, was talking to Gutfreund, who allowed that just about all the affair meant was “a few points on the stock.”

At the Wednesday board meeting, the directors heard a reading of a second press release, which included three pages of details and a straightforward admission that top management had learned of Mozer’s February transgression back in April. But a sentence that followed sent the directors into a telephonic uproar. It said that management had then failed to go to the regulators because of the “press of other business.” Buffett, listening in Omaha, remembers calling this impossibly lame excuse “ridiculous.” The explanation in the press release was later changed to incorporate the words “due to a lack of sufficient attention to the matter, this determination was not implemented promptly,” another passive-voice specimen slightly less lame but unflinching in its refusal to assign any blame.

‘THE ATOM BOMB’

The real offense of that Wednesday directors meeting, though, was not language but a flagrant omission: Gutfreund’s failure to tell the board that he had the day before received a letter from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that contained some doomsday words. The letter was signed by an executive vice president of the bank, but anyone reading it would have known that behind it stood 6 feet 4 inches of Irish force and temper, Gerald Corrigan, the bank’s president. Corrigan by then knew enough to have become incensed by these doings on his watch. The letter said that Salomon’s bidding “irregularities” called into question its “continuing business relationship” with the Fed and pronounced the Fed “deeply troubled” by the failure of Salomon’s management to make a timely disclosure of what it had learned about Mozer. It asked for a comprehensive report within ten days of all “irregularities, violations, and oversights” Salomon knew to have occurred.

Buffett learned later that Corrigan expected the letter to be promptly given to Salomon’s directors, whom he believed would just as promptly recognize that top management had to be changed. When the directors didn’t act, Corrigan thought they were being defiant–but instead, of course, they were simply in the dark. Buffett did not hear about any Fed letter until later in the week, when he spoke to Corrigan, and even then Buffett assumed the Fed had only sent a request for information. Buffett did not actually see the letter until more than a month later, after he heard Corrigan refer pointedly to it in congressional hearings.

In Buffett’s opinion, the Fed’s belief that its letter had been ignored stoked the fury with which the regulators came down on Salomon a few days later. There is no shortage, Buffett says, of “vital matters” that Gutfreund, Strauss, and Feuerstein kept from the directors in the previous months, all the while acting as if things were perfectly normal. But not conveying the Fed letter to the board was in his thinking “the atom bomb.” Or maybe, he says, a more earthy description fits: “Understandably, the Fed felt at this point that the directors had joined with management in spitting in its face.”

A ‘RUN’ ON SALOMON

You may reasonably ask what was going on in Salomon’s stock while all of this was transpiring. It was emphatically down, from above $36 per share on Friday to under $27 on Thursday, when the second press release rocked the market. But the stock was only the facade for a much graver matter, a corporate financial structure that by Thursday was beginning to crack because confidence in Salomon was eroding. It is not good for any securities firm to lose the world’s confidence. But if the firm is “credit dependent,” as Salomon was to an extreme, it cannot tolerate a negative change in perceptions. Buffett likens Salomon’s need for confidence to a mortal’s need for air: When the required good is present, it’s never noticed. When it’s missing, that’s all that’s noticed.

Unfortunately, the erosion of confidence was occurring in a company grown enormous. Salomon in August of 1991 had bulged up to $150 billion in assets (not counting, of course, huge off-balance-sheet items) and was among the five largest financial institutions in the U.S. Propping the company on the right-hand side of the balance sheet was–are you ready?–only $4 billion in equity capital, and above that was about $16 billion in medium-term notes, bank debt, and commercial paper. This total of about $20 billion was the capital base that supported the remaining $130 billion in liabilities, most of these short-term, due to run off in one day to six months.

The paramount fact about those liabilities is that short-term lenders have their track shoes on at all times: They have absolutely no enthusiasm for earning an extra fraction of a percentage point in interest if they perceive that their capital is even slightly at risk. Just waving a premium rate in front of them is in fact counterproductive, since it makes them suspect there is hidden danger. Moreover, unlike commercial banks, whose creditors can look to the FDIC or to the “too big to fail” doctrine, securities firms have no declared “Big Daddy” whose mere presence is a deterrent to runs.

So on that Thursday, Salomon began to experience a run. It materialized out of left field in the form of investors who wished to sell this big-league trader and market maker, Salomon, its own debt securities–specifically, the medium-term notes that the company had outstanding. Salomon had always made a market in these securities, but that was ordinarily a yawn, since nobody wanted to sell. But now the sellers poured in. Salomon’s traders responded by lowering their bids, trying to deter the traffic–dying to do that, in fact, because every repurchase of notes they made melted down the capital base that was holding up the whole Salomon structure. Finally, after the traders had bought about $700 million of the notes, Salomon did the unthinkable: It stopped trading in its own securities. That called a halt on the rest of the Street too. If Salomon wasn’t going to buy its own paper, it’s for sure nobody else would.

It was so bad at the time Buffett had to do a mea culpa before Congress.

Solomon recovered and was later sold to Travelers for $9B in 1997 (Buffett’s stake more than doubled).

It matters here because Valeant, for all of it issues has not broken any laws. We can make moral judgements all we want about drug pricing but the fact remains laws were not broken and they are at very little risk of a Chapter 11 filing. Sure, the media will make a huge deal out of the April 29th deadline but they will file before then and this risk is removed…

Remember folks, the media cares very little about the reality of any situation, they care most about ratings and nothing gets ratings like potentially huge drama.

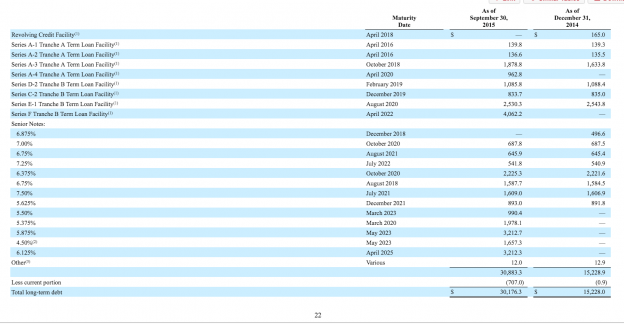

So, Valeant files it 10k and default risk is removed. So, where are we then? They have ~$1B in cash and practically no debt maturing in 2016, none in 2017 and ~$3.5B in 2018. Along the way they bring in ~$6B in EBITDA in 2016 and let’s call the annual number for 2017, 2018 flat so they earn roughly $18B EBITDA between now and before the first debt is due in August 2018 ($1.6B). Even if results fall, it would have to be an utter collapse for there to be debt issues. Additionally, all of this assumes they do not sell something between now and then to pay down debt early.

Then they have nothing until 2020.

The bottom line is they have a very long time to get their act together.

Valeant looks very compelling here. The stock collapse has stopped, the largest investor in on the Board now and there is a new CFO and CEO coming in. A top notch CEO with industry cred (think Hunter Harrison at Canadian Pacific) could turn sentiment about the company around instantly. We have to remember, even with its current issues, it is still a very profitable company for those buying shares here.

Whenever a big investor takes a hit, there are those who love to pile on and take their shots at them. From those who manage a pittance compared to these guys who even after their worst year have track records that soundly trounced those piling on, to the media who only manage maybe a checkbook to those bloggers whose sole existence in the world is telling us how everyone and everything just sucks (fortunately these are the minority of bloggers) it is their “Super Bowl of Schadenfreude”. It comes with the turf for those who manage billions. If you want to be at the top, you have to deal with those who only mission in life is to try to knock you off. Your choice is that or essentially hide like Seth Klarman does (anyone know his $LNG investment is down ~50% the last year?). They are no different that QB’s in football, when they do well, they are heros, when they stumble, they are bums. They are blamed for every action within the company when things go wrong. If a football team loses because a safety blows a coverage in the final seconds and the opponent scores to win the losing team’s QB “can’t win the big one”.

Likewise we are told Ackman should have known this or that about Valeant (even though he did not have a board seat until yesterday) and had social media been as pervasive in 1991 as it is today, these same people would have been claiming that since Buffett was on the Board at Salomon he must have known about the Treasury bid rigging and probably even endorsed it. At the very least these same folks would have painted him as utterly incompetent and derelict for not catching it. This of course would have been in spite of 99% of them having never stepped foot inside a corporate boardroom.

All that said, for value investors this piling on does provide opportunity. The cascade of opinion and coverage drives prices well below where they would have fallen without the incessant negative drumbeat (and conversely higher when everyone loves something). In times of fear or confusion, every negative article is given a “fact first” opinion until otherwise proven wrong. Separating the credible from the junk takes time and effort and selling a stock is far easier. So people sell. But again, this creates opportunity.

Wading in at prices far far below even a reasonable valuation gives one a huge safety net. People are convinced that default is a probable risk for Valeant now. I think in the case of Valeant simply filing a 10k by April 29th could be a huge positive for the stock. We do not even at this point have to get into debt repayment in 2020, drug pricing in 2017 and beyond or potential divestitures. At prices where they are, just hiring a CEO who has respect and filing a 10k can make you money….